Swing the Fly speaks with John McMillan to learn why he believes it’s crucial for Olympic Peninsula steelhead to be listed under the Endangered Species Act

Sitting on the tailgate of a truck in a light rain on the banks of one of the rivers of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula (OP), John McMillan doesn’t mince words. The now 51-year-old fish biologist confidently flows from powerful, passionate, often explicit metaphors to peer-reviewed scientific journal citations without skipping a beat.

“The time to seek solutions that are collaborative and behind the scenes is over. These fish need federal oversight in terms of not just management, but the habitat, too,” McMillan told Swing The Fly. “Do you think I want to write the obituary for the place I live in and love? It’s the last thing I want to do.”

The 2023 OP winter steelhead fishing season, which closed on April 1, will no doubt and unfortunately be remembered for much more than a few large fish.

On Feb. 10, National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) recognized a petition to list the OP Steelhead Distinct Population Segment (DPS) as a threatened or endangered species. The petition, jointly written by by McMillan, Science Director, and Rob Kirschner, Legal and Policy Director, of The Conservation Angler and co-submitted with Wild Fish Conservancy Northwest is a 164-page testimony on why now is the time to place such a listing on one of lower-48’s most iconic populations.

“The summer-run component is nearly extinct, and the winter-run component is declining and losing its life history diversity. The fate of the species now rests on a depressed and contracted mid- to late-spring component of wild fish whose productivity is limited or declining depending on the population. The remnants of these runs that historically numbered in the tens of thousands face declining freshwater and marine habitat conditions, increasing recreational fishing pressure and ongoing commercial harvest. Because of these and other demographic and ecological threats, Olympic Peninsula steelhead are likely to become endangered within the foreseeable future.”

Swing The Fly joined McMillan on that tailgate to discuss the straw that broke the camel’s back, issues an ESA listing could rectify and why he thought it was important to write it in a way anglers can understand.

What Triggered The Petition?

“It wasn’t until I had a better understanding of the historical context on abundance and run timing that my perspective began to change,” McMillan began, after a sigh, when asked if there were any specific moments when he realized a petition for listing was absolutely necessary.

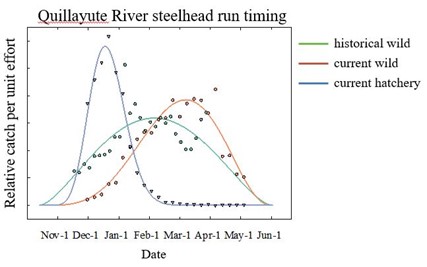

The proverbial awakening McMillan is referencing points to a study, Historical Records Reveal Changes to the Migration Timing and Abundance of Winter Steelhead in Olympic Peninsula Rivers, he recently published with Mathew Sloat of the Wild Salmon Center and Martin Liermann & George Pess of NOAA in 2022. In it, they analyzed multiple historical data sets ranging from 1948–1960 to estimate the migration timing and abundance of OP winter steelhead in the Quillayute, Hoh, Queets, and Quinault rivers in order to gain context for contemporary (circa 1980–2017) population trends.

“Based on those historical estimates (McMillan et al. 2022), the Quillayute, Queets, Hoh, and Quinault River wild winter steelhead populations have declined by 61%, 69%, 79%, and 81%, respectively, in relation to their most recent five-year mean run size. Those estimates do not necessarily capture the full extent of decline, however, because they came after decades of harvest and many years of habitat alterations,” the 2022 report states. “When compared to cannery data in 1923, for instance, the decline in the Queets River increases to 86%.”

So, what does true abundance look like? Using historical tribal and sport catch data, the 2022 study estimated that in 1954 over 50,000 wild steelhead flooded the Queets (the peak estimate for the study.)

“While peak calculations don’t represent the average, to give that pinnacle number some context take a look at the Skeena system, where a healthy modern-day run is considered about 30,000 fish — spread across the river’s mainstem and its crown jewel tributaries such as the Copper, Bulkley, Morice, Kalum, Kispiox and Sustut,” a Wild Steelheaders United article reporting on the 2022 study concluded. “The Skeena drains a mammoth 21,000 square mile basin. The Queets’ basin, in comparison, measures 204 square miles,”

McMillan added that in addition to gaining a greater understanding of the baseline for true abundance, the near elimination of the early run of winter steelhead in OP rivers was also of grave concern and cause for immediate action.

“The early-returning component of winter steelhead populations in the Quillayute, Hoh, and Queets Rivers is severely depleted and consequently, the breadth of run timing is now far more compressed than it was historically (McMillan et al. 2022),” the petition states.

In the traditional ecological knowledge of the Quileute Tribe the month of January meant the “time of steelhead running” and February the “strong time of steelhead spawning”

(Frachtenberg 1916)

In addition to numeric loss of fish returning early, the diversity of run timing – specifically early returning fish – is projected to have a crucial role if the OP is to continue to hold its place as one of the “last best” in a warming future.

“Steelhead enter and spawn earlier in the winter in warmer, more southerly regions of their native range (Busby et al. 1996), and as climate impacts progress, winter steelhead on the OP will also need to enter and spawn earlier to keep pace with climate change. Run timing provides one way in which salmonids can adapt to changes in stream flow and water temperature (Manhard et al. 2017), but that could be impossible for winter steelhead in the OP DPS if their original run timing is not restored,” the petition claims.

“Do we manage for the mean? Because variation in run timing is just as important as the mean,” McMillan claims. “What we have learned from science is that we can help reduce annual variability in run size by allowing all these smaller components – fish entering and spawning at different times and places – to express themselves and fill in gaps in productivity.

Managing for Viability Versus Redlining

“I hope an ESA listing can provide an objective examination of the population’s resilience and identify population features and habitats that require more attention,” McMillan responds when asked what an ESA listing could do for the OP’s declining stocks.

In Washington, steelhead are co-managed by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) and respective tribal co-managers. The WDFW Statewide Steelhead Management Plan (SSMP), approved in 2008, describes strategies intended to “help restore and maintain the abundance, distribution, diversity and long-term productivity of the state’s wild steelhead and their habitats to assure healthy stocks. To achieve this goal, the SSMP “establishes a series of policies to guide natural production, habitat protection and restoration, fishery management, artificial production, regulatory compliance, monitoring and evaluation, adaptive management, research, and education.”

The SSMP clearly states that steelhead management shall place the highest priority on the protection of wild steelhead stocks to maintain and restore stocks to healthy levels.

In their February petition, McMillan and co-signers showcase how current WDFW management is out of alignment with their own plan.

WDFW maintains a list – which the petition points out was last updated in 2002 – that describes the status of each stock as “unknown,” “depressed,” “critical,” or “healthy.”

“If a stock’s status is unknown, WDFW is supposed to “apply a precautionary strategy by implementing low risk fishery and hatchery management regimes. If the status is “depressed,” “critical,” or ESA-listed, WDFW should promote a trend of increasing wild fish numbers. If the status is “healthy,” WDFW should maintain wild steelhead escapement objectives at or above Maximum Sustained Harvest (MSH) levels,” the petition outlines. “Regardless of whether the nearly two-decades-old “healthy” status designations still apply to certain Olympic Peninsula steelhead stocks – which they do not (e.g., McMillan et al. 2022) – recent (2010-2021) escapement numbers indicate that WDFW is not maintaining escapement levels at or above MSH levels. For example, WDFW did not maintain Queets River wild winter steelhead escapement at or above MSH levels during the last eight out of nine years and have often failed to do so in the Hoh River. Further, they do not monitor or manage wild summer steelhead.”

Specific to hatcheries, in April of 2021, the WDFW Commission replaced Hatchery Policy C-3619 with a new Policy, C-3624 without State Environmental Policy Act review. This action is currently the subject of ongoing litigation. (Wild Fish Conservancy and The Conservation Angler v. Washington Dep’t. of Fish & Wildlife et al., King County Superior Court Docket No. 21-2-13546-0 SEA) ,

“Even after adoption, the new C-3624 hatchery policy is behind schedule on creating the evaluation protocols for the yet-to-be-developed hatchery management plans (HMP),” the petition explains. “Despite the known, ongoing harms that the steelhead hatchery programs are causing to the OP Steelhead DPS, no changes to relevant hatchery management plans have been proposed. Additionally, previous phased state environmental reviews are being abandoned, starting the decade-long process all over again.”

“Harvest and hatcheries. Those are dials we can turn,” McMillan told Swing The Fly, “to determine if we can rebuild early run time and levels of repeat spawners. To try and build resilience in our populations by diversification. We want the ability to take a truly objective look at how we’re operating fisheries and hatcheries. There’s no guarantee that an ESA listing will work, but there are examples.”

For instance, McMillan mentions Oregon coho which were in long-term decline before listing. In the late-1990s, after investing lots of money in habitat restoration and hatcheries to restore that decline, which wasn’t working, ODFW was forced to reduce ocean harvest and hatcheries. Then, when ocean conditions improved in the 2000s, Oregon coho returned in abundance levels not seen for over 50 years. Diversity and run time expanded, the habitat work they had worked on previously were being used.

“I understand the complexities. I’m not here to lay the blame. My point moving forward is that what we’ve done thus far hasn’t worked so let’s find something that we think gives us a better shot at recovery and that means experimentation.”

John McMillan

“The Feds often have some of the best scientists available. They can study fisheries in a way not all the state managers have the time and ability to do. We can see what managing for viability looks like, rather than the bare minimum. I mean. Come on. This is the fucking OP. If we can’t get it right here, then what hope is there elsewhere?”

The More We Know, The More We Fish

“That’s also why it’s hard to make a conservation case for somewhere that a lot of people generally think is doing pretty well,” McMillan told us, speaking to the comprehensive and exhaustively thorough nature of the petition. “It took eight months to write the petition. It was meant to be as thorough as possible, but it’s purposefully written in a way the common angler can read it and understand why we believe a listing is warranted.”

Here, McMillan pauses, his tone taking a more personal quality than academic. Like clockwork, the low clouds open up as McMillan reveals himself. Not just as a scientist, but as a proud member of a community and a lifelong angler.

“I think it’s important local people have a strong knowledge of the place and fish they love. That’s what place based management should be about and that’s what I think works. If you’re local, and I’d ask this of anyone, get involved. Even if you disagree,” McMillan says, speaking directly to his OP community. “Read parts of the petition. Search for knowledge. I don’t expect everyone to agree with me. Not at all. I’m fine with dissenting opinions. I think they’re crucial. But, I think local people need to be the most informed because this is their backyard and they can be, in many ways, a mouthpiece for the rivers.”

How about the thousands of anglers that continue to flock to the OP each winter while WDFW continues to need to close seasons early?

“Look, I’m not going to have the same expectation of people that are visitors, but if I had one suggestion, I’d ask them (visitors) to be skeptical. Think critically,” McMillan suggests. “Of me. Of your guides. Of the guy at the bar. I get it, you don’t have all the time in the world wherever you’re traveling, but I’d suggest learning about the place you’re traveling to by seeking out information from multiple sources! Introduce yourself to a few different arguments, debates and issues about the populations you are fishing for. Are they stable or declining? What are some of the major issues those populations face? Even some of the fishing books and magazines offer information on the fish and the fisheries. Knowledge doesn’t have to start with published articles and management plans.”

“Ultimately, this is a public resource, and while we are generally supportive of fisheries, we also think reducing our efficiency is important because that allows for longer seasons and the more people we have that enjoy the resource, the more advocates we have for wild steelhead,” McMillan says, his voice rising in a passionate crescendo. “But, implementing such fisheries, like on the OP the past few years, requires quality and timely information. We are not there yet, but better information can provide better in-season updates and offer greater certainty that we are operating fisheries that do not compromise the current and future resilience of the population. In general, diverse populations are more resilient and stable year-over-year, which is why we at TCA believe we need to account for diversity in management. Adaptive management won’t reverse all of the problems overnight, but it is a step. A step that can increase resilience and create stronger runs. A step to maintain the cultural love and practice that we have for this fish, for sport and tribal fishers alike.”

Currently, NMFS is conducting a comprehensive review of the best available scientific and commercial information before determining, whether, in fact, the petitioned action is warranted, within 12 months of recognition of the petition.

For now, McMillan returns to the river, 9-weight Burkheimer in hand.

“I alway want to reaffirm that I want people fishing. I love to fish,” McMillan said, taking off his sunglasses to reveal a glare that could only be described as the look of someone who’s had to defend himself for a long, long time. “That’s what we all want. Anglers are critical advocates for the fish. So, when we decided to petition, I want people to know we’re thinking about ‘how do we increase the odds that we’re fishing in 20 years.’ We think there are ways to fish, even when the runs are small. It just has to be managed creatively. I don’t want this to turn into some ultra-wealthy luxury, like in Europe, I’d like the average person to be able to go fish. I do appreciate the guide community and they serve a role. But, for most kids growing up in the NW, it was your dad taking you out and getting a fish. And eventually you learn to do it yourself, and there was enough fish to do that. I want that for everyone. For a long time.”